LOOK MoMA! NO HANDS: THE IRONY OF THE ARTIST’S ASSISTANT

Words by Anya Firestone

As published in Highsnobiety Magazine Issue 15 | F/W 2017

In today’s material world where hired helpers make high-art reach higher-prices, how might we understand the value of a “work” of art upon learning that its namesake’s creator might not have even worked on it during the creative process? When it comes to defining the responsibilities between the artist and his assistants, where do we, quite literally, draw the line?

Clara Lacey for Anya Firestone x Highsnobiety Magazine Issue 15

“I ask ‘cause I’m not sure: Does anyone make real shit anymore?”

In the sparkling halls of the Louvre Museum, where frescoed angels greet us on gilded ceilings and the hand-painted portraits of kings throw shade, we walk past art history’s greatest masterpieces, and painfully lament that, sigh, Kanye is finally right: They sure don’t make them like this anymore.

In the glamorous hodgepodge that defines today’s material culture, where luxury labels and Art Basel parties go hand-in-handbag, where JAY-Z films music videos in white-wall galleries, and where everyone coronates themselves as “creatives,” using words like “curate” to talk about Instagram, we have been Ubered to a point so obsessed with the concept of art, that today’s celebrity artists no longer even need to make their art themselves. I ask ‘cause I’m not sure—how can artists not make their art anymore?

We do not flinch when other big-time “creatives”—fashion designers, top chefs, or architects—employ assistants to materialize their concepts. We still say we are “wearing a Tom Ford” and Yelp that Chef Gusteau’s soup is the best in Paris, knowing well that the suit was made by a team of Polish seamstresses and tonight’s vichyssoise was prepared by the sous. Our expectations of the artist are different. He does not pass on a sketch like a recipe or a blueprint to his staff. He is the creative-creator, not creative-director, and his act of physical work becomes an inherent quality of the final ”work” itself. As he makes an artwork, it gains what theorist Walter Benjamin famously called its “aura,” its unique je ne sais qu’ality, its intangible heritage of the artist’s tangible experience which cannot be replicated.

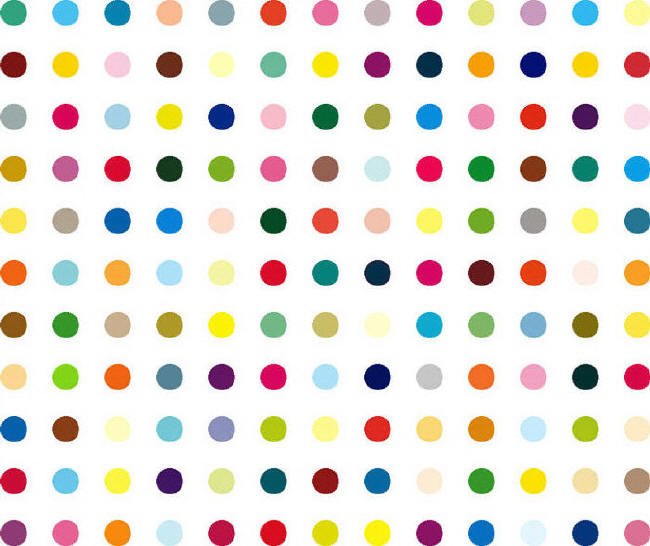

Surely the act of creating large and complex artworks—Da Vinci’s Last Supper, a 10-foot-tall KAWS sculpture, or a Damien Hirst canvas of 10,000 perfectly painted dots—is physically demanding in scope and time, and thus ameliorated by having helpers. Yet how do we justify the instances when the artist is acting more like a big-name fashion designer, not only calling for extra hands, but sometimes not even putting in his own? In other words, when an artist materializes a concept as a painting, sculpture or installation with the aid of his workers, does the physical process with matter even matter anymore?

Art History is no stranger to the art-worker phenomenon, and for centuries its biggest OG masters relied upon a slew of helpers to complete most of the world’s famous artworks. While Michelangelo was painstakingly painting the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling from 1508-1512, he did so with the aid of his trusted assistants, who jungle-gymmed across ladders and scaffolding to finish his frescoes. And so it was that the many famed talents represented on the Louvre’s walls today—Titian in the 16th century, Rubens and Rembrandt in the 17th, Fragonard and Jacques-Louis David in the 18th—all hired (and fired) numerous apprentices to help create the masterpieces that defined their careers.

Jacques Louis-David, The Coronation of Napoleon, 1805-07, Musée du Louvre

Unlike today, back when the aristocracy had its head on its shoulders and the Louvre was a king’s palace and not a museum, artists were not creating for the sake of art itself, therapeutic release, landing a Louis Vuitton collab, or high sales goals at Basel. Rather, they worked because they were commissioned by ruling royals and religious figures of the land to create historic paintings of battles, biblical scenes, and handsome royal portraits to fill castles and cathedrals. To execute such monumental projects, assistants became as critical of a support system for the artist as were his easels.

The National Gallery’s curator of Dutch paintings, Axel Rüger, explains: “Rembrandt ran very large workshops with pupils who had to pay for the privilege. There’s no way that one artist could have cranked out those hundreds of paintings, so they would work with assistants, and a master’s crucial touches to painting were sometimes even contractually determined.” This relationship was equally advantageous, and even pedagogically necessary, for the assistant. Today, a quarter million-dollar fine arts degree cannot even guarantee an internship at Gagosian (you likely need a Masters for that and a well-connected family). And unlike those who constantly attempt to “disrupt” the dominating styles of the time, aspiring creatives since the Renaissance, and centuries after, were scrupulously trying to perfect them.

Back then, the art world was a tightly controlled faction, led by academic jurors and eventually kings like Louis XIV, who regulated artistic production by imposing certain master’s techniques to follow (the brushstrokes of Rubens or the lines of Poussin—the 1617 “battle of the styles”). Like hip-hop artists who build entire careers on sampling, the fine artist did the same, eager to be shown at the salon and eventually commissioned by an emperor. In sum, simulation, as opposed to innovation, was the original MO to professional artistic success.

After the fall of the aristocracy, academic art would fall into disfavor and rising rule-breakers like the Impressionists painting en plein air had little need for studio assistants, let alone the need for a studio. Gaining traction again in the 20th century, artists have upped the need for basic backup; prime the canvas, mix the paints, clean the edges—and in more recent history, operational tasks—call Gagosian, plan the exhibition, pass the Xanax, make a video, plan the Basel party, post on Instagram.

Today, assistants in media and technology help artists extend their work into newer areas. An artist like Jeremyville has a hand that is so present in his art that he often creates it live (like in the vitrine at colette in Paris during his solo show). “My art is a lot about the process, the way it is made, and the moment in time each piece represents,” he explains. Yet despite his physical proximity being tantamount to the work, Jeremyville calls upon casting experts with new technology to assist him in translating his drawings into three-dimensional cast objects, like a seven-foot-tall fiberglass sculpture. “All approaches to me are valid. The art is in choosing the right tools and medium to get the idea across,” he adds.

Similarly, artist OLEK, known for her hand-crocheted public artworks, will sometimes use hundreds of hands as a tool to create massive installations that bring attention to social issues such as equality; when she crocheted an entire women’s shelter in India, a train in Poland, or covered an 80-foot-tall Obelisk in Chile, assistantship provided pragmatic help while contributing to her greater goal to “transform the process of making art from a solitary act to a collective adventure.”

OLEK and her assistants crocheting a massive installation, 2013

In sharp contrast, British multi-millionaire Damien Hirst hires dozens of workers to create his iconic spot paintings—white canvases covered in thousands of perfectly painted, randomly chosen colored circles. There is no new media applied here, nor any meaningful social message about the process (socialism is another story). Artist David Hockney openly rejects those who pay talent to make art which is sold solely under their name, arguing it is “insulting” to the craft; after publicly criticizing Hirst for doing so, Hockney installed a sign at his Royal Academy exhibition that read: “All the works here were made by the artist himself, personally.”

Damien Hirst, LSD, 2020

If “artists” like Hirst depend upon human workshops to make their art for them but still get the credit (and the paycheck), does this mean that anyone who has a good idea for an object, and the money to fund a warehouse filled with MFA grads to make it, suddenly merit a solo show at the MoMA? Not really.

Despite the fact that many may hold Hockney’s traditional view of the “artist,” we are obliged to confront the mightier voices of art history—the institutions, academics, curators, collectors and gallerinas who ingratiate these obscenely priced, otherhand-made works into their gallery atria, coffee table books and Hamptons homes. For we have reached a critical moment in material culture wherein the single artwork to hold the highest auction record by a living artist, is a sculpture made by an artist who did not make it.

Enter Jeff Koons, into his high-ceiling Chelsea art studio where he directs more than 100 studio assistants who ‘Work it, make it, do it, harder-better-faster’ for him, meticulously executing phantasmic oversized art pieces like shiny balloon dogs, pop-esque paintings, and giant lobsters that resemble pool inflatables on which every “creative” on Instagram wants to be photographed.

“We have reached a critical moment in material culture wherein the single artwork to hold the highest auction record by a living artist, is a sculpture made by an artist who did not make it.”

Jeff Koons, Cracked Egg

John Powers, a previous “serf” of Koons, described factory-like conditions when he painted Cracked Egg, part of Koons’ ‘Celebration’ series. After four other staffed-painters color-matched and labeled each hue and gradient for his use, Powers took a paintbrush-head the size of an eyelash to meticulously create a manufactured-like perfectly executed surface for $14 an hour. He likened the task to painting by numbers. Jerry Saltz, artworld provocateur and senior art critic for New York Magazine, has praised some of Koons’ paintings “for looking like they’ve never been touched by living beings but have been made by scores, maybe hundreds, of hands, almost transcending human touch, for their mutilating of ambiguities.” In 2003, the Cracked Egg sold at Christie’s auction for just over half a million dollars, cracking the record as Koons’ most expensive work at the time.

If we follow Saltz’s train of thought, and reason that it is the concept of uncredited craft itself that holds mysterious value, then the bigger question at hand, quite literally, becomes phenomenological: How can we conceptually grasp, or even attempt to justify, that an anonymous exertion of labor could be proposed as an artist’s valid “technique” of fine arts practice?

This is not the first time history has questioned the paradoxical validity of a work art by an artist who did not make it. A century ago, in 1917, French artist Marcel Duchamp took a manufactured urinal, signed it “R.Mutt,” and put it (upside-down) on display. The avant-garde gesture insinuated that the act of physical creation was not necessarily the responsibility of the artist. A readymade became the artwork Fountain because Duchamp selected and placed it in an exhibitionary context, creating a new thought for that thing. The work was completed not by the machine, nor the artist, nor his assistant, but by the viewer himself, what Duchamp calls the “artist’s coefficient,” who finishes the creative act upon contemplating the absurdity of that thing as proper “art.”

Andy Warhol extended Duchampian avant-gardism. He fetishized the everyday mass-manufactured goods—the Brillo pad and Campbell’s soup can—to create a spectacle of banality, as he felt that the images of great art, like the masterworks in the Louvre, had become so overly reproduced and circulated that the originals were reduced in history to visual clichés. In his New York studio dubbed the “Factory,” filled with drag queens, porn stars, socialites and anti-socialites, Warhol developed various “hands-free” modes of art-making. Mechanical methods like photography, printing and silkscreening allowed him to displace his own hand a certain distance from the work so as to emulate mass production.

“I am working on every level, artistic, commercial, advertising,” he said. Warhol was not using the machine to make art. He was the machine. “I am nothing and I can function!” he said.

Koons, contrastingly, thinks he is something and does not function. He admits to the fact that he lacks the talent to execute the work and thus removes himself from the painting and sculpting processes altogether. “I’m basically an ideas person,” he explains, “I’m not physically involved in the production. I don’t have the necessary abilities, so I go to the top people.”

Saltz recalls witnessing Koons in a Madrid club a decade before Cracked Egg was painted. “I watched him confront a skeptical critic while smashing himself in the face, repeating, ‘You don’t get it, man. I’m a fucking genius.’” Then, exactly a decade after Cracked Egg sold at Christie’s, Koons’ Balloon Dog Orange, a stainless steel-coated sculpture assembled and polished by his creative Keebler elves, shattered the world market with a record $58.4 million sale. How have we ended up here? So high but feeling so…low? Art history allowed Duchamp to turn the readymade into art, and for Warhol to turn the artist into a machine. And now, what about Koons? What has he done?

The highest grossing creative of our day has succeeded not with readymades, but with “ready maids,” applying, an ironic, extraordinarily traditional, hands-on approach to crafting an artwork—just not doing the “work” himself. So is he a genius? The answer, just like his craftsmanship, absolutely does not matter. Instead, what matters is how we can comfortably call a “Koons” a “Koons” if Koons did not make the “Koons?”

How we can comfortably call a “Koons” a “Koons” if Koons did not make the “Koons”?

It is one of the art world’s finest riddles, and to attempt an understanding, or a challenge, is not to question why the assistant is present, but more so, how the artist is absent. In other words, when we raise our paddles to bid on “a Koons,” what is it that we are truly buying, or rather, buying into? Art in the name of craft, or art in the name of concept? It seems, just art in the name of the name. For this artist did not make art; instead, he made art history, and created its biggest brand name of all: Jeff Koons. “Just as Koons was a positive emblem of an era when art was re-engaging with the world beyond itself,” Saltz explains of the artist’s career evolution. “He is now emblematic of one where only masters of the universe can play.”

And now we are here, back in the Louvre where we started, humming to the sound of Kanye West’s “Stronger.” This time, we are next to the Mona Lisa celebrating “The Masters,” a 2017 art collaboration by Koons for Louis Vuitton, seated at an ironic dinner party that, after Da Vinci’s Last Supper, merits nomination as art history’s most significant scene of consumption.

While Koons has participated in brand collaborations before, from Supreme to Dom Perignon, those projects have only recontextualized his own (assistant-made) artworks. This time, importantly, Koons is not putting his own Balloon Dog on a handbag like he did for H&M, but instead reappropriating art history’s greatest hand-painted masterpieces on luxury goods. Comprising 51 pieces, including the brand’s classic handbag models like the Speedy, Neverfull, and an assortment of wallets, keychains and scarves, The Masters Collection features images of some of the world’s most famous artworks by artists like Rubens, Titan, and Da Vinci selected by the man of the hour.

“Bow in the presence of greatness,” sings Kanye.

Let us recall that in the days of the Masters, art was made because rulers paid for it. Beyond being decorative work for the elite, it was also a propagandistic visualization of power, wealth and religion. So must we be stunned that half a millennia later, the art world operates under parallel circumstances, creating luxury forms of visual branding for the wealthy all-stars of their times just in a new, and quite literally, contemporary fashion?

“And just like that, Louis Vuitton has replaced King Louis as the art world’s golden demagogue sovereign, without even having to leave the Louvre building.”

Big names and bigger concepts of art have always defined material culture; now, they come back again as materialism proper, on a $4,000 luxury handbag, notably hosted and accepted by one of the most famous art institutions in the world where it all started. And just like that, Louis Vuitton has replaced King Louis as the art world’s golden demagogue sovereign, without even having to leave the Louvre building.

Listen oh would-be art historians, sneakerheads, luxury marketers and self-proclaimed creatives! If the artist has evolved into a luxury brand, then where does that leave the future of art? Turn your attention to see what has become not of names but of art itself, the world’s biggest cultural signifier of power, fame and fortune! See how we have praised the artist’s hand (and often unknowingly, his assistant’s) and then look down to find a messenger bag in your own, carrying all the baggage of intangible value itself.

How do we attach multi-million dollar tags to one name with hundreds of anonymous hands? Or, when will someone admit that we cannot, and have just been Punk’d by art history in the world’s most expensive joke?

Jeff Koons “Masters Collection” celebrated at a private evening at Musée du Louvre

Exiting the museum, we double-kiss Bernard Arnault au revoir, and, pass a sign that reads “DO NOT TOUCH THE ART,” and exchange a sinister smile with Mona Lisa as we grab our Koon’s clutch. On the bag, the iconic face of Lisa Gherardini still grins, just now beneath large, gold-plated metallic letters: DA VINCI. They glisten like a hip-hop artist’s bling, reminiscent of Lil Jon’s legendary diamond necklace that reflectively spells “CRUNK AIN’T DEAD.” Here, DA VINCI is not a signature nor even an artist anymore, but a word on a commemorative tombstone, a sign of a no longer existing sign system, and a visual signifier that while “ART AIN’T DEAD,” the artist’s responsibilities are, and have been resurrected anew.

As DA VINCI sparkles on the clutch, wedged between the golden “LV” monogram and Koons’ own initials, we cannot help but LOL at the irony of his intertwined letters; styled just like the company’s signature logo, Mona laughs right back at us, as they visually proclaim: JK!

“‘Cause it’s Louis Vuitton Don night, So we gon’ do everything that Kan like. ”

Words by Anya Firestone