DECK THE WALLS: THE RISE OF THE SKATEBOARD X ARTIST COLLABORATION

Highsnobiety Magazine Issue 13 | F/W 2016

Words by Anya Firestone

As street culture and high art magnetize towards one another exponentially, the [skateboard × art] collaboration signifies their acute meeting point in the 21st century. I took an in-depth cultural studies approach to rethink what the resulting object stands for, on behalf of contemporary branding and the future of art itself.

Rolling on skateboards and across hip-hop, at streetwear popups and in sneaker drops, contemporary branding has been cast under a creative spell, or perhaps curse, of the C-word. Just as “curation” has become a trendy term, decontextualized from its museological origin and misused across street culture (mostly as a poser-synonym for “arrangement”), so too has “collaboration” acquired powerful new impact in the space where curating first began: the art world. Today, the phenomenon marks a historic moment for both domains: in a dangerous liaison between low and high culture, we find the skateboard hooking up with artwork, and as a result, being curated on a wall as if it is one.

Regardless of whether we consider the decked-out skatedeck as objet d’art or not, it is almost precisely because we are so unsure that its existence marks a critical era for all players involved: for street culture, and its unquestionable move into elitist spaces; for art itself, an object on the brink of yet another identity crisis; and lastly, for art institutions — the galleries, auction houses, and foundations that seem to acknowledge and even ingratiate these objects into their histories (or at least, into their gift shops).

Art history is no stranger to the collaboration phenomenon, and many of its most prominent players have participated: Modernism gave us prolific works by Matisse × Derain, Cubism: Picasso × Braque, Abstract Expressionism: Johns × Rauschenberg, even in the 17th century Rubens’s portraits and Breughel the Elder’s landscapes linked up to form Flemish masterpieces just as Warhol and Basquiat created paintings, sculptures and installations in the 1980s. Yet in all of these instances, the motives and tastes of each creator — philosophical, aesthetic or otherwise — were somewhat analogous. Furthermore, unlike in fashion, for example, where creative collaborations usually result in mass production, collaboratively made artworks guard their uniqueness and singularity, no matter how many creators.

Today, as couture houses cross-pollinate with sneaker brands and sporting goods (Saint Laurent and Marc Jacobs both released skate decks in SS16 and ’15 respectfully) we see art following suit, entering new relationships, or, like the “design collective” Vetements, wild orgies with popular culture brands. From liquor labels (Hennessy V.S × KAWS) to streetwear (Raf Simons × Sterling Ruby), couture (Dior × Marc Quinn) to mass-fashion (H&M × Jeff Koons), and even to hip-hop (Sotheby’s × Drake), art hops from hoodie to high-top with newfound passion, like a swinger at a swanky nightclub called #Collaboration.

From all the unlikely bedfellows that art would find itself on top of, the skateboard is perhaps the most perplexing. While we can compare the resulting object to the [sneakers × artist] dropping daily, from a material-culture perspective, a skate deck by mega-artist Damien Hirst has a different narrative and impact than a pair of kicks by him. Something known to “tear up” and “shred” walls would seldom find itself on the same exact space of a painting, historically created to do the opposite. Ontologically speaking, the work of art and the skateboard are not only different, but are inherently contradictory.

Art, first commissioned by kings and emperors, has been born into a privileged culture in royal palaces and temples, from Mesopotamia to Ancient Greece and up to the French aristocracy. Beyond being decorative, art was also didactic, operating aesthetically and conceptually as a sign of supremacy: of god(s), kings, and the law. In sum, during the first defining touchstones of its history, art itself was a solid program of visual branding for the high-culture powers-that-be, from Rameses to the Apostles to Napoleon.

The skateboard, contrastingly, was born out of a counterculture. In the 1960s, it entered the scene rail-sliding on park benches when the surf was too low and grinding in empty swimming pools during the LA droughts. While it was an object found in an exclusive circle, it was not rooted in elitism nor did it function dogmatically for the masses. Rather, the skateboard was a material good that moved against the grain of society and avoided mainstream integration (the sneaker, on the other foot, ran right in). As the skater scene developed a grunge and punk flair throughout the 1990s, its visual history that followed evoked its bad-boy temperament, with skull decals, violent doodles and tits. Not even Nike can claim to have successfully infiltrated the skater group until about a decade ago, with its SB shoe line launched in 2004. On the high-low material-cultural spectrum, while art started from the top, the skateboard started from the bottom.

And now we are here: at the Summer ’16 Sotheby’s contemporary auction in Manhattan, scratching our heads with our paddles wondering what three skateboards on the wall are really doing here. The triptych before us, a collaboration between contemporary artist Takashi Murakami and Supreme, is estimated for sale at $3,000-$5,000. Supreme has a history of engaging in high-cost collaborations, and even went so far as to host a retrospective in 2013, where skateboards made by Richard Prince, Christopher Wool, George Condo, Larry Clark and Jeff Koons, amongst others, hung on a wall encased behind glass, curatorially mediated like delicate gems at the museum.

During the first defining touchstones of its history, art itself was a solid program of visual branding for the high-culture powers-that-be, from Rameses to the Apostles to Napoleon.

There are more than a few street-elite-savvy brands producing limited-edition decks today, such as Boom Art, Mood Board and The Skateroom, to name a few. Unsurprisingly, there are many more art critics and collectors who reject the authenticity of these collaborations as valuable to art history, dismissing them not as art, but a cheap fetishism of it by brands acting like “posers.” Yet if such is the case, then there is a troubling incongruity regarding the willingness and desire of the artists to get on deck. The creatives are not just graffiti or street artists like Nick Walker or “The Gonz” (both of whom are very logical choices), but notably today’s highest grossing museum-represented figures such as Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst and Ai Weiwei.

It is undeniable that the collaborations expose artist to new audiences who might not otherwise be familiar with them (except maybe from a Jay Z lyric). It is also clear that brands can (or at least try to) elevate their own identity by virtue of the highvalue association. Regardless of who is using whom, it makes us wonder about the raison d'être of the mysterious object that follows, and whether or not it is art or just artifact branded to look like it. Even if the artist is just a superficial marketing tool used to turn hay into gold, is there a way that the gold can be “real?” In other words, how can we imagine a skateboard, that which was born as high art’s opposite, to possess or extend art’s inherently unique qualities — those that distinguish it from pure commodity — notably, its conceptual, aesthetic and intellectual prowess that it has accrued over millennia?

Enter: The Skateroom, the first company formed on the basis of [skateboard × art] collaborations and the one whose specific aim is to preserve and proliferate the importance of art. So how do they do it given an unlikely meeting with art’s opposite?

With a conceptual goal to mix “the energies of a legendary underground culture and legendary artists,” the company, founded by gallerist-turned-philanthropist Charles-Antoine Bodson, pairs up with artists such as Paul McCarthy and Ai Weiwei, street artists like D*Face and Futura 2000, and foundations such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol to produce, promote and sell limited-edition skate decks. Yet by virtue of its unique business model and its artistic choices, The Skateroom shows us how its collaborative object can function not to undermine, but rather to conserve, if even marginally and widely ironically, the value of art and its history.

To this end, the company’s profits fund establishments like the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and museums such as the Museum of Modern Art, Tate, and the Guggenheim, all of which share a mission to display, conserve, and promote art and its history. Secondly, the company functions philanthropically, by supporting Skateistan, an NGO founded by skateboarder Oliver Percovich, with a mission to “empower vulnerable youth through art and skateboarding.” Skateistan creates schools and projects in Afghanistan, Cambodia and South Africa for children at risk where “youth come for skateboarding, stay for education.” The company explains, “We offer artists a new and different support for contemporary art and the opportunity to link their art with a good cause.”

Yet in addition to their philanthropy (the limited edition Paul McCarthy decks just enabled the creation of Skatesian’s new school in Johannesburg), The Skateroom formed a collaboration that ironically fosters artistic ideologies because of their placement on a skateboard, which we would fear would do the opposite.

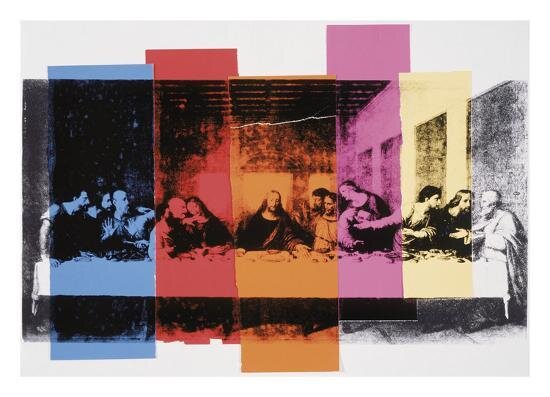

The Last Supper, Leonardo Da Vinci, c. 1490s

Notably, the company teamed up with the Andy Warhol Foundation, established in 1987 in accordance with the namesake artist’s will “to promote the advancement of the visual arts.” Together, the two forces produce various singular and multiple skateboards sets using the artist’s iconic works. Recently, they dropped what perhaps exemplifies the very issue, or resolution, of the [skateboard × art] collaboration: a set of three decks that together depict the center detail of Warhol’s 1986 painting The Last Supper.

Warhol’s painting, inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s 15th century masterpiece of the same title, was not, contrary to popular misunderstanding, about the masterpiece; rather, it was about that masterpiece’s overexposure. In a sort of Postmodern mindset (which sounds like “ART IS OVER!”), Warhol recognized that on account of the machine in the modern age, great art like da Vinci’s mural had become so overly reproduced and circulated, that it was iconoclastically de-aestheticized and reduced to a cliché. He visualized this opinion by creating his painting from a screen print that depicted a cheap photograph that depicted a mass-made 19th century engraving that depicted the original 15th century artwork. Levels.

The Last Supper, after Da Vinci, Andy Warhol, 1986

Overall, Warhol’s Last Supper was a work of art that acknowledged the sad truth about art’s over-reproduction and as such, a sort of “ending” to art’s image in the modern world. So what happens when Warhol’s visualization of the problem of reproduced and commodified art ends up being reproduced itself – and not on a canvas, but on art’s ontological nemesis, a withdrawn, consumer street good?

“I'm in the hall already, on the wall already/ I’m a work of art, I'm a Warhol already,” Jay Z raps in “Picasso Baby.” The Skateroom, like Jay, acknowledges the significance of Warhol as one of the most prolific figures in art history. And we cannot deny that mainstream culture has already become so inundated by his image just like we have been by da Vinci’s paintings. But the joke is on us if we see a skateboard as the final gesture to subvert what Warhol’s genius masterpiece signifies. Au contraire! we cry on behalf of art theory, because the image of it reproduced on the deck logically extends Warhol’s very own message one step further. Perhaps the skateboard’s finest trick.

Art hops from hoodie to high-top with newfound passion, like a swinger at a swanky nightclub called #Collaboration.

Coincidentally, Supreme released a set of decks with The Last Supper on it, but theirs was a direct blown-up snapshot of da Vinci’s original. Similarly, boom art created decks with images of high art Renaissance works, such as Hieronymus Bosch’s famous Garden of Earthly Delights as well as The Lady and the Unicorn, one of history’s most iconic wall-tapestries commissioned by the French aristocracy in the Middle Ages. While these are fantastically decorative objects, they function aesthetically as whimsical appropriations of art, and do not operate conceptually by extending the “aura” or message of the original like those by The Skateroom.

Warhol took the everyday object and commercial brands — the Campbell’s Soup can and the Brillo Pad, for this reason: the gesture was his attempt to create anew, to make an event out of banality since the holy patriarchs and Mona Lisa were already done with. And he succeeded not because he competed against the machine, but because he was the machine. “I am nothing and I can function,” he said, “I am working on every level, artistic commercial, advertising…” Warhol’s art was groundbreaking because it was a sign of a no-longer existing sign system. If [skateboard × art] collaborations are authentically impactful when the art used announces its very usage, then we can look also to the decks by Paul McCarthy and Jeff Koons, artists whose repertoires extend a sort of Warholian belief about art’s metaphysical nihilism in the modern world.

The Last Supper by Andy Warhol, The Skateroom

As The Skateroom’s Warholian Jesus sits on the triptych, extending his arms over the decks, he blesses the very objects upon which he finds himself. His gesture points not only to the skateboard’s holy ascension from dried out Los Angeles to a mural of angels but also to those very angel’s simultaneous descent into street culture. Indeed, art has come a far way from its elitist origins, and any attempt to redefine "art supremacy” today makes us flip up, flip out and land some place paradoxical, in between the Louvre and Supreme.

We can be optimistic on behalf of material culture that art has become increasingly fashionable as a result. But what does it signify if art is acting like fashion too, moving from painting to skateboarding like couture moves to streetwear? If today’s fashion collaborations are becoming fashion themselves, do we take this as a warning that collaborations will signal the future of art? The Vetements Spring/Summer 2017 collection is the perfect allegory for the concern: during this past couture week in Paris, head designer Demna Gvasalia hosted a gluttonous feast of an impressive 18-brand spread, including Canada Goose, COMME des GARÇONS, Brioni, Manolo Blahnik, Levi’s and Reebok (the latter two also collab’d with Gosha Rubchinskiy the same season). The results were as mixed as the smörgåsbord of its participating labels: while the Blahnik “Sky-High” waist-high boots showcased outstanding new heights, quite literally, in bilabel liaisons, Vetement’s rhinestone Juicy Couture look may have at best garnered a giggle, nostalgic #TBTracksuit, or a throwing in of the towel (or, terrycloth zip-up) to collaborations altogether.

We need not cross ourselves with the collaborative letter “X” and declare that one more sentence with “art and skateboard” will be art’s death sentence, for it is clear we do not need a conception of art to exist for us to decide to work in a mode that we could nominate as “art.” In other words, if there was no phenomenon called “art” we could still validly propose a mode of working that would turn out to be just like it (but without the name), lifting the encumbrance of the historical art to begin anew.

Yet how can we imagine novel ways in which something like an art can be made, shown, displayed, used and contemplated, without being fully pressed to ideologies and enigmas like conceptual art, or else reproduced, branded and stepped on in an ironic secondary market — or worse, H&M?

And who will show us the way? Is it the artist? The curator? The collector? Sotheby’s? The Skateroom? Jay Z? Until that messiah arrives, we must continue to digest what contemporary culture is serving us — from an 18-brand feast at Vetements to an ironic Last Supper — and consider it food for thought for purists and posers alike. And so, as we stand in our Nike SBs during Art Basel only to find The Skateroom’s decks at the Beyeler Foundation, we can choose to look the other way, back to the holy book of art history, or else just hop on board, and roll with it.

Words by Anya Firestone