DAMAGED GOODS: THE DRAW OF THE HIGH BRAND X STREET-ART COLLABORATION

Highsnobiety Magazine Issue 14 | S/S 2016

Words by Anya Firestone

As graffiti tags markup handbags and ball-gowns, the liaison between luxury labels and street artists marks a critical shift in both fashion and art history. I used an art-theoretical lens to see how a runaway on the runway may paradoxically resurrect, or else bury alive, the heritage of both high and low cultures.

If history repeats itself, then art history has painted the same picture time and again: an artist invites in a muse to inspire and elevate his work; Jeff Koons got Lady Gaga just like Vermeer got his girl with a pearl earring. Today, the artist has also become contemporary culture’s own muse, being summoned by fashion and lifestyle brands seeking to enhance their image through his artful input. Some results have been museum- and CFDA Award-worthy: Cindy Sherman extended the eccentricities of COMME des Garçons, Richard Prince’s painted nurses morphed into models giving life to Louis Vuitton, and French conceptual artist Daniel Buren illuminated the house of Hermès with his silky light installations.

Yet we find ourselves at a runway crossroads when faced with the most recent expression of the trending [brand x artist] collaboration formula: namely, when a high-end brand turns not to high art, but rather to the street artist, as its collaborative muse. Since the early 2000s, we have seen and felt the rebellious itch scratched onto upscale surfaces: Stephen Sprouse spray-tagged Louis Vuitton’s classic monogram, KONGO’s bubble letters bombed Hermès silk the next decade, GucciGhost haunted Gucci with sardonic graffiti last season, and soon RETNA’s glyphic markings will cover a limited edition cashmere blanket by Hale Harden in the fall of 2017.

Few can deny that there is something inherently unsettling, something overtly faux pas, when an old-age institution steeped in glamour and tradition invites in a notorious vandal whose values and aesthetic lie far outside the realm of luxury; quite literally outside. A renegade marking his space with tag and spray seems a world away from a couturier whose tag reads MADE IN ITALY, and whose spray exists only in the form of eau de parfum.

If we are to excuse the fashion world for simply following suit with the ebb and flow of the art world, then we might come to terms with one reason why brands pursue street artists more and more. Since the turn of the 21st century, the genre’s domination of visual media has risen both in the institutional and financial sectors; this is evidenced by exhibitions such as the groundbreaking show on the history of graffiti at MoCA in 2011, as well as by six-figure sale points at fairs and auctions worldwide. The same year that Jeff Koon’s Balloon Dog (Orange) sold for a record-breaking $58.4 million at Christie’s New York, the elusive British Street artist Banksy was believed to already have a net worth of $20 million in sales. London gallerist Steven Lazarides, who helped catapult Banksy’s career, notes the genre’s distinctive state today: “I can walk into collectors’ houses and see a Francis Bacon, an Anish Kapoor and a piece of street art.”

Banksy, I Can’t Believe You Morons Actually Buy This Shit

On behalf of our sanity, and art, we have every right to question when a wheat-paste sticker is peeled off a brick wall, taken to auction, and ends up hanging on a Park Avenue mantlepiece. Even graffiti artists ask the same thing: the day after three of Banksy’s works sold at Sotheby’s London, the artist released a print drawing depicting a room full of bidders, before a picture that reads I Can’t Believe You Morons Actually Buy This Shit (needless to say, that print later went for sale at Sotheby’s, too). While street art under curation may seem dubious, the oxymoron only intensifies when it comes under collaboration. First, because the artist himself is always an active participant, and secondly, because there exists a brand at the receiving end of that gesture who incorporates the image as part of its own.

It is logical that a company with similar roots in genres like hip-hop or a subculture like skateboarding would invite a graffiti artist to design its products. The STASH x Nike Air Force 1s or the Skateroom x ROA decks are just two of countless examples of balanced street-for-street liaisons. Yet in the same 2017 season that DJ Steve Aoki debuted his streetwear line in New York, with pieces by graffitist David Choe (whose “bullet wounded” trench-coat was worn by skaters, not models), Paris showed us a more questionable rendering of runaway-meets-runway at the house of Dior.

Collection Homme for Dior by Dan Witz

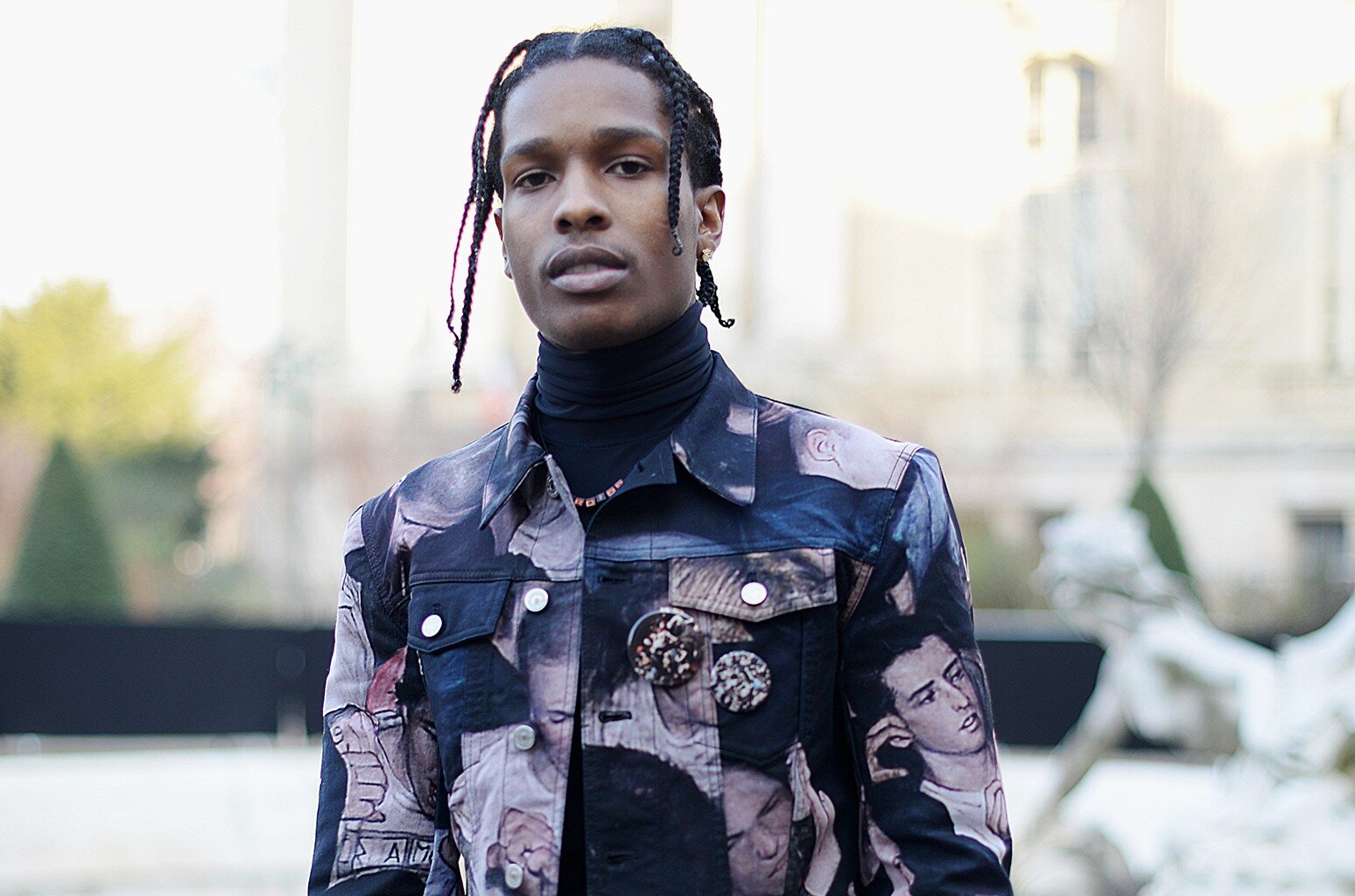

A$AP Rocky in Dior x Dan Witz

Located at the elegant Musée Rodin, and exactly sixty years since Christian Dior debuted his iconic New Look, we encountered a very new look for his brand: A$AP Rocky, the New York hip-hop powerhouse as its newly-enlisted face, donning the house’s latest collaboration of a head-to-toe “Mosh Pit” motif of layered, sweaty bodies by street-artist Dan Witz. Beside him stands creative director Kris Van Assche, who has just posted a Dior skate deck on his Instagram, with a new trending hashtag, #HARDIOR.

We pause to deeply consider, like Rodin’s Thinker sculpture in the museum’s garden, the physical, or rather, metaphysical impact of this [brand x art] moment: What results when two disparate entities, with polar opposite energies, originating from fundamentally opposing origins, magnetize towards one another at a prolific rate, and then, poised and ready to collide, explode at Fashion Week, shred the runway, and land next to Anna Wintour’s bob as it nods to the beat of Fashion Killa?

Salvador Dalì, The Persistence of Memory, 1931 (Museum of Modern Art)

It goes without saying that Dior has reigned as one of the most proactive fashion houses of art patronage. In the 1920s, long before his days as a couturier, young Dior was a passionate gallerist who sold works by the likes of Giacometti and Magritte, and was the first to exhibit Dalí’s famous painting of melting clocks, The Persistence of Memory, in 1931. When Dior moved from high art to high-fashion over a decade later, he still turned to the great painters for inspiration, designing looks named for Matisse and Braque in 1947. Since then, the house has maintained a tradition with art on the runway and in its stores: from Raf Simons’ ready-to-wear and haute couture collections featuring Andy Warhol and Sterling Ruby respectively, to the new London flagship by architect Peter Marino, decked with as much contemporary art as merchandise.

Graffiti. Gangsta. Hip-hop. Street. New York. Why does the French house align itself today with such a radical ethos? Do brands like Dior really need a level of street cred in order to get by, and be bought, in contemporary culture?

According to Dior Homme’s artistic director, cultural adaptation is part of the house’s necessary evolutionary process: “Fashion isn’t about taking codes or ideas and simply putting it on today’s stage,” van Assche explains, “it’s about taking them and reinventing them, re-purposing them for today.” To do so, he designed the collection with a heavy lineup of street art graphics, including paint-splattered sneakers, pieces “embroidered with scars,” “daubed with white paint” and Witz’s work, then enlisted A$AP Rocky to put it all on, emphasizing what the brand notes as the “collection’s rebellious spirit.”

Rebellion can be sexy, like Sandra D at the end of Grease. It is also a force that keeps the art world spinning. Many of art history’s most beloved painters began their careers as rule-breakers. El Greco dismissed Michelangelo’s modes of representation and got backlash from Rome just as the 19th century Impressionists revolted against the French Académie des Beaux-Arts: Monet was shamed. Degas was denigrated. Seurat was rejected from the Paris Salon. And in the 20th century, after Dadaists like Duchamp rebelled against art practice by simply exhibiting everyday “Readymade” objects, the second half of the century birthed groups like Minimalists and Post-minimalists, who rebelled not only against previous forms of representation, but forms altogether.

Street art takes rebellion even further. Rather than operating against a previous space in art history, it rebels against space itself: the street, sidewalk, subway; the un-institutionalized open road. Since the late sixties, while the genre typically, but not always, manifested a somewhat aggressive aesthetic, it was the art practice itself, the act of making it and putting it down illegally— therein lies the aggression that comes to define the genre. In other words, its ontological existence, what it is to be “street art,” is based less on its content than on its context. The street artist known as “Space Invader,” as its species’ nomenclature, would sum it up. As street art takes shelter, moving inwards into luxury handbags and filtered with hashtags, how can the disruptive genre persist within the determinants of its own existence if its public reception takes place neither on the street nor illicitly?

Banksy reasons, “For the sake of keeping all street art where it belongs, I’d encourage people not to buy anything by anybody.” Yet there is something inherently ironic about Banksy’s statement: the notion of “where it belongs.” In fact, the very concept runs contrary to the sentiments of a true street artist, whose work is most often made under the supposition that it inherently does not belong. While Banksy suggests street art should remain in the spaces it intervenes, can it not, and should it not, intervene in other spaces?

The question is phenomenological. And the answer goes beyond a marketing expert’s idea of “authenticity.” Rather, it involves the art-theoretical notion of “the aura,” a concept coined by Walter Benjamin in his seminal essay of 1935, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. The aura helps us to understand why the Mona Lisa is the most famous painting in the entire world, why no copy of it can ever possess the same magnitude: because of the painting’s unique existence in context—who made it, owned it, stole it, saw it, and hung it up. A bootleg Birkin or a forged Basquiat—strap for strap, stroke for stroke—will never be as valuable as the original because it lacks its true circumstance and history, its “aura”; what Benjamin explains as the artwork’s “presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”

For the street artist, context is everything. “Doing graffiti on a canvas is like domesticating a wild animal” says artist Faust, known for his illicit letters in urban spaces. Yet if the doors a graffitist tagged swing open to an atelier in Paris, why should he not walk in like Alec Monopoly and graffiti his shtick all over the Birkin inside? And if he does, would that aggressive mark on a handbag or even an entire fashion collection, in an ironic twist of events, be the street artist’s greatest bombing? If so, do we deem the brand just ‘a rebel with a KAWS?’ Simply put, the moment the brand gets graffitied in the attempt to be edgy and cool, is it really just getting Punk’d by its edgier, cooler, cultural nemesis?

The moment the brand gets graffitied in the attempt to be edgy and cool, is it really just getting Punk’d by its edgier, cooler, cultural nemesis?

GucciGhost for Gucci

Gucci’s recent 2016 collection consciously, unabashedly and very sarcastically took this moment as momentum. In one of the most clever collaborations between a high-end fashion house and a street artist, its creative director Alessandro Michele tapped ex-Olympic snowboarder Trevor “Trouble” Andrew, AKA GucciGhost, to vandalize the collection with his cartoonish Gucci skulls, ghosts, and fried eggs across furs, sweatshirts, and even the windows of the New York flagship.

The collection can be summarized by one piece: a leather tote bag, embossed with the Gucci logo, upon which dripping painted letters intervene, spelling “REAL.” While we can read the “REAL,” most obviously, as the brand’s clever nod to its own history and tumult in a world that has copied and proliferated its logo to exhaustion (fake ‘Guchi’ can be found on the corner of 57th, two blocks away), something else takes place if we look at it with an art theoretical lens. Namely, it is not just the brand’s declaration that its aura is REAL, but in fact, the artist’s. GucciGhost is actually carrying out the street artist’s mission: to mark territory, to mock culture, to occupy space, to vandalize, as the model carries that gesture down the runway.

“A true writer, a true vandal, is going to think that way,” says Will Atkinson, a former street-art gallerist and current director of a high-end design gallery, Maison Gerard. “At the core of street art, it’s the goal to take space in new areas.” Extending this notion, Maison Gerard recently invited Faust to graffiti a twenty-one foot long wall as the backdrop of its art fair booth in the venerable Winter Antiques Show, a prestigious art, antiques, and design fair held in New York City’s posh Park Avenue Armory.

“I saw it as an opportunity to turn heads and make an impact in the stodgy setting,” explains Faust on his reason for doing the piece. Choosing “a more nuanced palette” of silvers and grays as opposed to his typical black and white high-contrast works made for the streets, Faust nonetheless guarded the wild spirit of his practice in this collaboration. While his curvaceous dripping letters glimmered and dripped beautifully behind the gallery’s deco pieces, they simultaneously, and cunningly, intervened in their context. Faust explains, “I revisited a piece I originally did on the street in downtown Brooklyn that said It seemed like a good idea at the time in response to the financial crisis of 2008, this time corresponding to the inauguration of Trump.” Appropriately, the fair opened on inauguration day, a few blocks north of Trump Tower; as the Muffys, Vanderbilts, and sable-clad shoppers walked by Ming Dynasty relics and Chippendale mirrors, Faust’s piece perfectly intervened it all. The joke was not on the artist. It was on the space.

As we admire the elegance of Faust’s letters shining on the Upper East Side, perhaps we can also rejoice how highend lifestyle, even if being influenced by street, influences the street back. When it comes to quality, a handful of brands are applying the most refined forms of craftsmanship to streetwear and sneakers. KOIO Collective, a newer company to the footwear scene, makes their buttery leather high and low tops in the same Italian factory as Chanel, with a quest to “make a shoe that merged the finest old world craftsmanship with the aesthetic of young New York.” As such, while they elevate the sneaker on a pedestal, quite literally, in their retail space they call a Sneaker Gallery, KOIO will add an artistic edginess in their first upcoming collaboration with tattoo artist JonBoy.

Similarly capitalizing on the street-elite fusion, LA brand Hale Harden creates hoodies, T-shirts and beanies entirely from only the highest grade of cashmere yarn, sourced in Italy by its founder Hale Hines. For his first collaboration, Hines tapped his neighbor, graffiti artist RETNA, who previously created pieces for brands like Louis Vuitton, to put his iconic glyphic marks on a cashmere blanket. Positioning the blankets as “tagged and touchable artworks,” only ten will be made, each with a different color palette (and with a high-art five-digit price tag). Hines, with a rebellious grin, notes, “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve wanted to touch the art on the walls of museums just because I’m not supposed to.”

And now we are here. Standing behind a sign that reads DO NOT TOUCH at the MoMA, next to Dali’s The Persistence of Memory, first exhibited by that young gallerist named Dior. As its melting clocks and herds of ants suggest the passing of time, and with it, decay, we look down to our graffiti splashed sneakers and wonder: how much of Dior’s memory really persists? Is it inevitable that this is where it ends up?

What would the ghost of Dior say as his brand lives on without him? Did he smile back at the Mona Lisa while watching Simons’ fifth Dior womenswear runway held at the Musée du Louvre? Perhaps he might even love Dior Homme’s Spring/Summer 2017 collab with Japanese artist Toru Kamei, where blossoming flowers with eyeballs look back at us like Lisa, and even like Dali’s fantastical creatures. Accordingly, he might praise Van Assche today for the Surrealist aspect of the Dan Witz collaboration, too. If so, does this mean that Kanye West really is a divine prophet like he thinks, having chanted Christian Dior Denim Flow years ago?

Yet if we take GucciGhost’s skull and crossbones doodle as a greater sign of luxury’s REAL cultural demise, its Fashion Killa proper, how would Saint Laurent react as his house shifts from shift dress by Mondrian to skateboard by Slimane? Would the spirit of Balmain condemn his eponymous brand for keeping up with the Kardashians instead of with his own artistic vision? And what of Monsieur Vuitton, the canvas-trunk maker who worked when Napoleon III reigned supreme: does he roll over in his grave as his monogrammed casket becomes the new canvas for Supreme? And who gets the last laugh? Barbara Kruger?

As we exit the MoMA in our $800 high-tops, wondering if we were in fact the morons for actually buying this shit, we can at least go home and sleep well, tucked under a cashmere RETNA, knowing that It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time.

Words by Anya Firestone